February 2021 Vol. 76 No. 2

Features

1950s Pipeline & Distribution Construction: Record-Setting, Booming Business

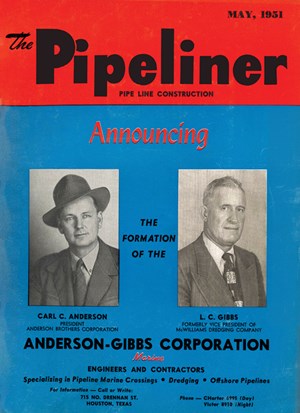

75th AnniversaryUnderground Construction’s first incarnation as the “Pipeliner” continued with booming growth throughout its first full decade of publishing – the 1950s. By the end of the decade, the magazine had broadened its coverage of underground infrastructure and was renamed Pipeline Construction and Oliver Klinger Jr. became the new publisher.

The robust pace of pipeline construction in the late 1940s intensified throughout the 50s decade, repeatedly setting records on its way to becoming a billion-dollar business. By the end of the 1950s, construction plans in the United States and Canada totaled $2.2 billion.

That included nearly 14,000 miles of crude oil pipeline – dominated by big-inch, long-distance trunklines – more than

in any other decade and about double in future decades.

With equally active pipeline construction, natural gas became a major fuel in the U.S. for the first time. In 1954, utilities were reporting gains of 800,000 customers a year and by 1957, the American Gas Association reported natural gas was providing 23.1 percent of the nation’s energy, versus 12.6 percent in 1945.

At the end of the 1950s, more than 1 million miles of natural gas distribution pipelines had been installed, compared to just over 25,000 miles the previous decade.

There were so many projects, in fact, that the steel industry couldn’t keep up with the demand for new pipe. Shortages that existed from the beginning of the decade were exacerbated by the nation’s heavy involvement with the Korean War. As a result, the Petroleum Administration for Defense established an allocation system in 1952 that gave first priority to pipe for oil, then natural gas.

Modern technology

Technology was, again, a major factor, making pipeline construction faster and more efficient, and enabling the industry to venture into areas no one had ever dared dream of – through tough rock or crossing wide, deep rivers – as the nation continued to expand into rural, often-barren regions.

In 1951, for example, International Harvester of Chicago and Superior Equipment of Bucyrus, Ohio, used pipe booms to slide 800-foot sections of 22-inch pipe for a project bringing Canadian oil to market through the swamps of Minnesota. “Mushin’ through the Muskeg,” the Pipeliner called it.

A pipe bending machine introduced by M.J. Crose Manufacturing (Tulsa) in 1953 – using a vertical, versus horizontal, plane – saved time, and produced a much smoother and accurate bend compared to existing machines.

It could also handle pipe larger than 20-inch diameter, as demonstrated by a loop program, in 1954, for the first time using 36-inch pipe in long-distance transmission.

By the mid-1950s, new pipeline coating products – using hydrocarbon polymers –improved performance in the underground environment. Also, application technology that enabled the first pre-fabrication of fully coated spools, was recognized as an industry changer with a major benefit and boost for production and lay.

New trenchers were also expediting many jobs, Pipeliner reported. In 1955, for example, Ditch Witch Power was equipped with a patented “endless conveyor digging chain” design that enabled it to be operated by one person.

Small buckets with sharp, finger-like edges were mounted in sequence on an endless moving chain that carried each bucket downward to chew out chunks of soil, then upward to dump the spoil in neat piles on the ground. A 4-inch-wide trench with a digging depth of 24 inches was the goal. The operator sat on the machine and used simple lever controls to raise and lower the digging device.

A year later, M.J. Crose Manufacturing introduced a machine with a novel, rotatable head for digging into dirt, sifting out coarse material and directing it to a conveyor or the like prior to laying the pipe. In addition, a pad protected the pipe against damage from rocks and other materials during the subsequent ditch-filling operation.

In 1957, Jim Cummings, co-founder of Crutcher-Rolls-Cummings (CRC) Inc., invented a dragline ditch padder that protectively encased pipe to be buried underground during evacuation backfilling operation.

That same year, Case Construction Equipment produced the first fully integrated backhoe loader, versus attachments added to loaders or farm tractors.

Projects evolve

Projects during 1957 and after continued to make significant strides, geographically and technologically.

In the aftermath of the Suez Canal crisis, representatives of 17 major American and European oil companies mapped out a 1,500-mile crude pipeline from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean via Iraq and Turkey. Its purpose was to reduce dependence on the Canal for Mideast Oil and to bypass more volatile areas like Egypt.

Williams Bros. built the largest all-welded line ever constructed for gas transmission, two 55- inch, 13-mile steel lines bringing coke oven gas into a Pennsylvania steel mill.

A unique river crossing in Philadelphia, with 13 products lines in one trench, was completed for Gulf Oil Co.

That same year, the magazine detailed new techniques for offshore and marine pipelining. “Magic,” the first sea-going lay barge designed specifically for offshore work in the Gulf of Mexico, was commissioned by Marine Gathering Co. of Houston, in 1957. Texas Eastern Transmission established a record-breaking cut on a 30-inch main line across the Rio Grande to reach into Mexico’s rich gas fields.

In 1958, Canada completed its 2,240-mile Trans-Canada natural gas pipeline – the world’s longest, at that time. Running from Alberta to Montreal, through some of that nation’s most rugged terrain, the three-year project was also the toughest and most costly system in pipeline history.

Southern Natural Gas announced plans for a $110 million expansion, its largest ever. A Westcoast transmission line brought the first gas into British Columbia and the Pacific northwestern states.

Other work progressed, as well. In 1958, contractors completed the first interstate ethylene pipeline, extending from Lake Charles, La., to Orange, Texas.

By the next year, all the major pipeline companies were listing big expansions ranging from $20-million projects to Trans Western Pipeline’s $193-million expansion bringing Texas and Oklahoma gas to California.

Harbert Construction (Houston) began work on a 2,600-mile system from McAllen, Texas, to Cutler, Fla., through snake-infested swamp lands. It would comprise Florida’s first gas line and be the longest pipeline project under construction in the world.

Transco also completed a record with the first dual crossing of a major river (the Hudson) using pipe as large as 24 inches. The 4,200-foot job took less than a week, another record,

In the last year of the decade, the magazine included photos of Williams Bros. contending with a 78-inch water project in St. Louis and started discussing pipeline prospects in the deep water.

Magazine Matures with Industry in the 1950s

From the start of the decade, Pipeliner was well-ahead of its competitors. Its circulation – at 4,600 – was more than double what it was when it debuted in October 1948 and was growing by 256 subscriptions a month.

It was also far larger than the competition in size, now boasting 80 pages per issue. It remained focused on jobs, with “Contracts Let” running 30 pages.

Another top priority was pipeline projects. Pages were filled with details on the plans and progress of major construction. And special Construction Reports highlighted everything from river crossings to new compressor stations.

It supported the burgeoning industry’s meetings and events. The January 1950 issue extensively covered the November 1949 PLCA convention, as the magazine would all future association sessions.

Technology was an increasingly important factor. In addition to highlighting its role in projects, the magazine published its first technical paper in January 1950: “Double Jointing Large-Diameter Pipe Speeds Up Pipe Line Construction,” provided by Floyd Berry, a welding engineer.

Color

In 1951, Pipeliner displayed its first full-color page ad, by Midwestern Constructors Inc. About a year, ads describing the latest in telecommunications and microwave systems began appearing in the magazine.

Following his father’s death in 1954, Oliver C. Klinger Jr. assumed the role of publisher and maintained the magazine’s legacy of evolving with the pipeline industry. In 1956, its name became Pipeline Construction, to reflect its focus more accurately. The changes in content and format enhanced its popularity and influence.

One was the addition of full-page editorials. Examples include a far-sighted warning, in 1957, that although pipeline construction was one of the five top industries in the country, jobs were increasingly starting later and ending early, forcing many highly skilled workers out of the business. The magazine urged the industry to retain contractors for maintenance and repair, thus enabling contractors to keep key personnel on the payroll year-round.

Another editorial, also in 1957, speculated on the pipeline industry of 1975, predicting that pipe diameters would push 60 inches and ditching would create development of ultra-sonic disintegrators to pulverize soil and rock for removal from the trench area by suction. Instead of welding, it envisioned that abutting pipe ends would be combined through an ultra-high frequency sonic process.

Further enhancement came from adding “News of Note” columns covering important events and issues, such as in Washington, D.C. In 1956, for example, a column reported on the Federal Power Commission’s decision that arbitrarily lowered a negotiated price of natural gas from producer to transporter and issued one of the first industry calls against government interference to normal business standards. Referred to as the “Memphis decision,” it was reversed in 1958.

Safety was another topic for “News of Note,” such as the American Standards Association’s 1959 publication of the first code exclusively dedicated to the transportation of liquid petroleum products and crude oil. (Currently, this code is referred to as ASME B31.4, 1998 Edition.) Separate codes for pressure piping evolved during the late 1950s, in recognition of the increasing complexity and diversity of pipe needs in various industries.

Comments