April 2014, Vol. 69 No. 4

Features

Reviewing OSHA Trench Safety Requirements

It’s an everyday occurrence on the job. Whether you are the contractor, the inspector or even the engineer you may have to get in a trench. Most of us don’t give it a second thought and get the job done. Trenches however, are a dangerous environment and accidents can occur quickly and often without warning. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) states that fatality rate from trench related work is 112 percent higher than general construction work. A basic knowledge of trenching and the dangers it presents is essential to staying safe.

There are different types of trenching. The first is an open trench where the sides are usually back-sloped, depending on the soil type. This trench may have steep walls for the majority of the excavation but includes “bell holes” where it anticipated that workers will need to enter the trench. Another type uses a prefabricated shoring box that provides protection for workers. The trench box is moved as the work progresses forward. These are used in congested areas where there is minimum space to work in.

The final type of trench uses constructed on site methods such as sheet piling and cross bracing. These are used for deep excavation and for areas where groundwater may present a problem. They are usually designed by an engineer.

Regardless of the trenching technique OSHA requires a “competent person” to be on site. OSHA defines this person as “an individual who is capable of identifying existing and predictable hazards or working conditions that are hazardous, unsanitary or dangerous to employees, and who has authorization to take prompt corrective measures to eliminate or control these hazards and conditions.”

After you have identified the trench type, you should asses the possible hazards. This includes ingress and egress. There should be an easy path such as a gentle slope or a ladder so you don’t fall in the event you have to exit the trench quickly in an emergency. Exposure to vehicle and heavy equipment is another hazard. Heavy equipment next to a trench can cause an otherwise safe wall to collapse. Falling objects are another hazard to be aware of. Hazardous atmospheres and confined space issues should be addressed. The trench should be monitored for the presence of poison or explosive gases. The final item to watch for is the stability of the soil and how it may change with influences such as weather conditions.

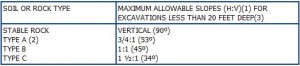

OSHA has a classification system for soil types and maximum slope depending on the cohesiveness of the soil. These correspond to accompanying chart. The first is stable rock. This includes excavations in rock where there is little danger of loose rock falling. Class A soils are very cohesive and are composed of material such as clay, silty clay and sand clay. Class B soils include cohesive and some non-cohesive soil such as loams and angular gravel. Previously disturbed soils and loose rock may also fall in this category. Type C soils are sands, loose gravels and saturated soils with low to no cohesion.

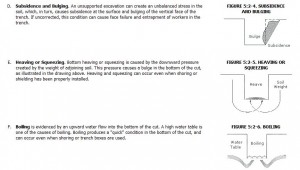

According to OSHA soils may fail in a number of different modes. These are shown in items A thru F

Trenches can be a dangerous area that we often overlook. If you have any questions you should consult the competent person onsite or an engineer. More information may be found in the OSHA Technical Manual (OTM) Section V: Chapter 2. Keep an eye out for changing conditions that may result in a hazardous situation. Always remember: if the trench does not look safe then don’t get in it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Russell Spruill is a registered professional engineer with the state of Missouri. He holds a B.S. of Science in Civil Engineering from the University of Missouri – Columbia and a Masters of Public Affairs from Park University. He has 18 years total experience ranging from heavy equipment operation to design and construction engineering. He is currently employed with the federal government at the Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration – Office of Pipeline Safety.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect to the views of the United States Department of Transportation (DOT) or the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA).

Comments